“Changing from sculpture into human being:”

Lorenza Böttner’s Venus de Milo

ESSAY

ISSUE I

2025Gemma Cirignano

Art historian

Issue I, 2025

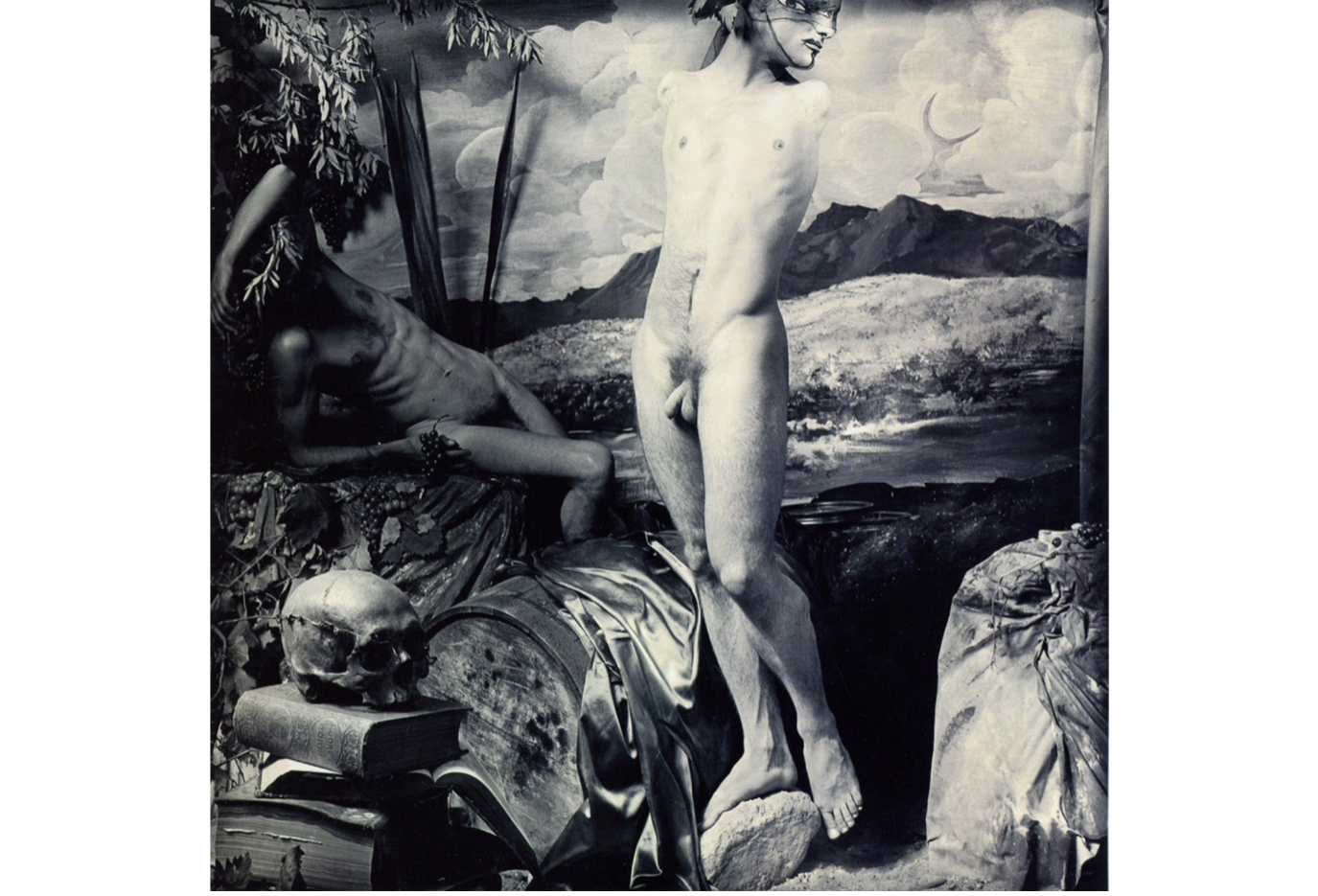

“What would you think if art came to life?” Lorenza Böttner opens her eyes and asks before she descends from a two-stepped pedestal on which she silently posed as the Venus de Milo for nearly twenty minutes. Painted in a thin layer of white plaster and dressed in nothing but a delicately folded sheet around her low waist, Böttner performs a committed, if not fully convincing imitation of ancient Greek statuary. Her angular jaw, rudimentary breasts, and narrow hips, accentuated by the chalky plaster, betray an element of masculinity; however, her arm-free shoulders with one donning a plaster prosthetic bicep that truncates just below her breast reassure the viewer that she is, in fact, the fragmented Hellenistic sculpture. It is not until the artist leaves her post that the same feature, which once assured her viewer becomes unsettling, and her fragmented body becomes unnatural (fig. 1, 2).

In 1959, Böttner was born into a male, nondisabled body in Punta Arenas, Chile. [1] At the age of nine, she gripped an electrical pilon while reaching for a bird’s nest, a mistake which resulted in the amputation of both of her arms.[2] This Icarian accident—another recurring mythological subject for Böttner—led her first to Santiago de Chile’s hospital for surgery and then back to her family’s home country of Germany for a series of treatments at the Heidelberg Rehabilitation Center and the Orthopedic Rehabilitation Clinic in Lichtenau.[3] Böttner rejected the centers’ shared goal of “normalizing” her body and chose to draw and paint with her mouth and feet rather than wear prosthetic arms.[4] In 1978, she began her formal art education at the School of Art and Design in Kassel and introduced dance and performance into her practice. At art school, she changed her first name to Lorenza and started identifying as a woman.[5] Until she died of AIDS in 1994, she lived and worked as a trans, disabled artist and created drawings, paintings, photographs, and performances that explore her intersectional body.

Böttner introduced her Venus de Milo performance in 1982 as part of her thesis show in Kassel. In 1986, she restaged the performance in New York City, first informally in the East Village and then for a charity concert at Hunter College.[6] The full performance begins with the artist already in position on the pedestal. As the audience fills into the theater, two lamps, one emitting blue light and one emitting green light illuminate the artist/statue. After five minutes of stillness, a rope slowly pulls the pedestal forward.[7] When she arrives at the edge of the proscenium, Böttner opens her eyes and speaks, an action she identifies as: “changing from sculpture into human being.”[8]

Böttner moved to New York City after receiving the Artists with Disabilities grant to further her education in dance and performance at NYU Steinhardt in 1984. To support herself, she drew and sold large pastels, many of which were self-portraits, on the street in Manhattan. One of these untitled pastels from 1985 illustrates herself once again as the Venus de Milo (fig. 3). Like in her performance, Böttner draws herself as a marble statue, carving out her shadows with subtle hues of black and blue. Her arm-free torso, this time forgoing the prosthetic bicep, curves into a gentle contrapposto, and her three-quarters turned head tilts slightly downward. Her gaze, however, lifts back up to meet that of the viewer and her slight smile acknowledges, perhaps even greets it.

In a performance description, Böttner spells out the paradox of the Venus de Milo she interrogates how: “a sculpture is always admired even if limps [limbs] are missing, where a handicapped human being arouses feelings of uncertainness and shame.”[9] This contradiction has become an object of study for disability scholars, most notably Lennard Davis, who challenges art historians’ “amnesia” to mutilation in sculpture. He claims that in overlooking disability in art, particularly in the tradition of the nude, art historians promote a hegemonic division between good and bad bodies (and body parts).[10]

Böttner’s Venus de Milo performance remains absent from Davis’ writing and the dominant discourse in disability studies. Instead, Davis cites the Irish artist Mary Duffy’s (1961-) performance and photographic series Cutting the Ties That Bind, 1987 (fig. 4), notably created five years after Böttner’s first performance.[11] Duffy, a double amputee, cis woman, also invokes the Venus de Milo as she poses silently, breaking the illusion of statuary only to confront her staring audience: “You have words to describe me…Congenital malformation.”[12] Her homonymous series of photographs portrays the artist at various stages of undress that capture her identity as she shifts into and then back out of the Venus figure. Despite the striking similarities in Böttner and Duffy’s methods and intentions, no evidence suggests that the artists knew of one another.

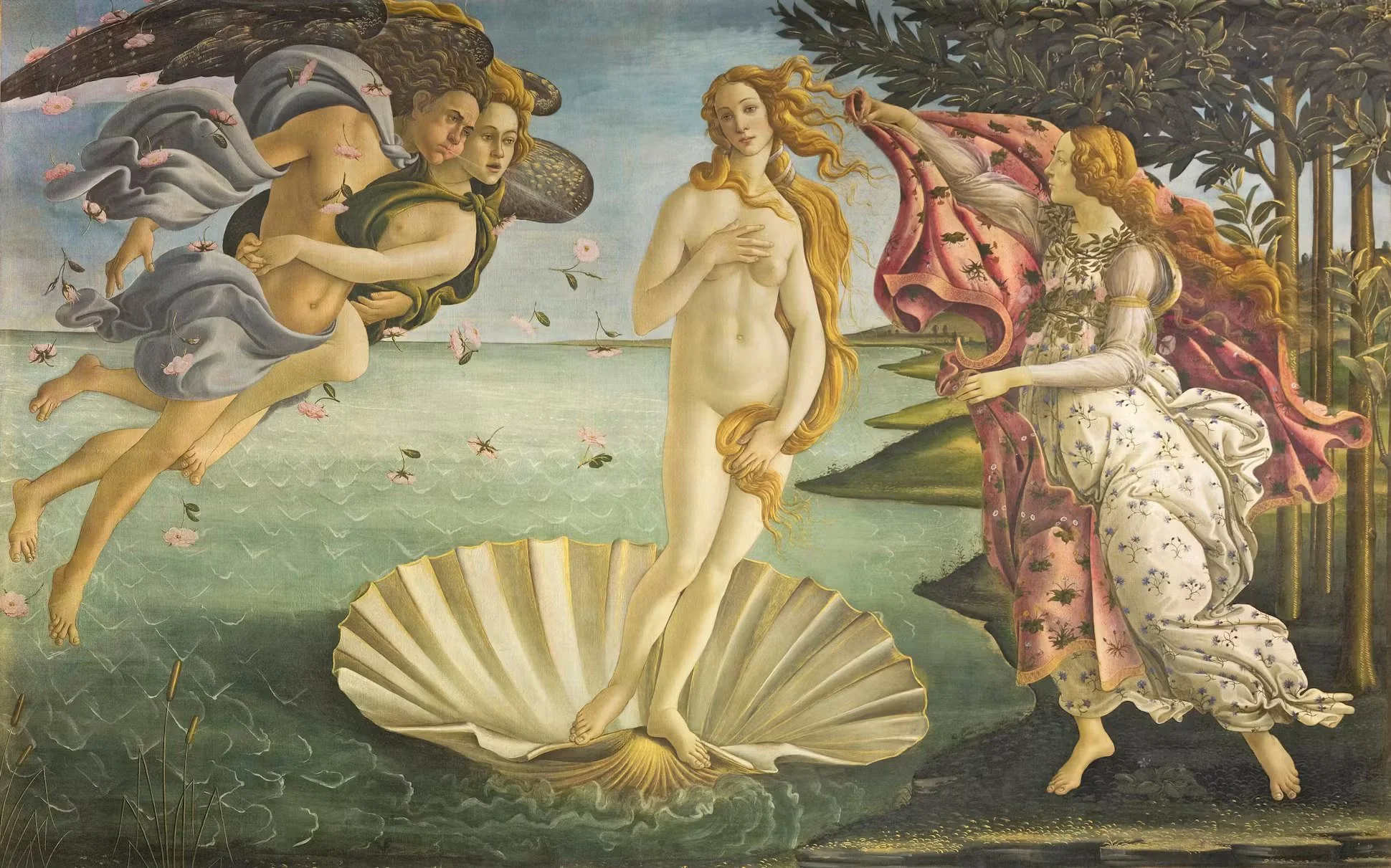

The American artist Joel-Peter Witkin (1939-), on the other hand, knew Böttner personally. Before his explicit reference to the Venus de Milo in his photograph First Casting for Milo, 2003 (fig. 5), Böttner modeled for Witkin’s Bacchus Amelus, 1986 (fig. 6). Centrally positioned in the photograph fully nude and contrapposto, she echoes a more Botticellian Venus.[13] However, unlike Birth of Venus (fig. 7), her face is obscured by a mask, and she cannot cover her genitalia with her delicate hands, thus exposing her penis and flat pectorals. Witkin, a nondisabled, cis man, has been both critiqued for his fetishization of amputees and praised for his subversion of the medical gaze.[14] The latter has been extensively argued by Ann Millett-Gallant, whose scholarly interest in the disabled Venus has led to a prolific bibliography on the topic that once again overlooks Böttner.

Given the contexts in which she performed, Böttner’s prescient Venus de Milo received no critical attention during her lifetime, a key factor in her canonical exclusion from disability studies and art history.[15] One must also wonder, however, how her queer and disabled existence compounded this striking erasure. Böttner proposes an embodied Venus not only arm-free but also without breasts and with a penis. She challenges the ableist, cisgender gaze to redefine Venus no longer as a static allegorical ideal but as a living multidimensional human being. In embracing disability, Böttner strengthens her identity as a disabled person, a trans woman, and a visionary artist.

1

Paul B. Preciado, Lorenza Böttner: Requiem for the Norm (New York: Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, 2022), 4.

2

Lorenza Böttner, Lorenza: Portrait of an Artist, directed by Michael Stahlberg, (Kassel, Germany: Seed Pictures, 1991), 3:25-4:05.

3

At the Orthopedic Rehabilitation Clinic in Lichtenau, Böttner’s treatment was integrated in with that of children of Thalidomide-addicted mothers, a drug which, if consumed while pregnant, causes abnormalities to the fetus’s limbs. Preciado, Lorenza Böttner: Requiem for the Norm, p. 4.

4

Preciado, Lorenza Böttner: Requiem for the Norm, p. 3.

5

Lorenza was the feminine form of the middle name she was assigned at birth.

6

Paul B. Preciado, Lorenza Böttner: Requiem for the Norm (Montreal: Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery, 2021), p. 12.

7

Böttner notes that if the venue is not equipped for this pully system, she will walk slowly towards the public.

8

Lorenza Böttner, performance description of Venus de Milo, 1987, Archive of Alabama Halle, Munich, Germany.

9

Böttner, performance description of Venus de Milo, 1987.

10

Lennard Davis, “Nude Venuses, Medusa’s Body, and Phantom Limbs: Disability and Visuality,” in The Body and Physical Difference: Discourses of Disability, ed. David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), pp. 53, 57.

11

Davis, “Nude Venuses, Medusa’s Body, and Phantom Limbs: Disability and Visuality,” p. 51.

12

Mary Duffy as quoted by Ann Millett-Gallant, The Disabled Body in Contemporary Art (New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2010), 25.

13

Carl Fischer, “Lorenza Böttner: From Chilean Exceptionalism to Queer Inclusion,” American Quarterly 66, no. 3 (2014), p. 754.

14

Ann Millett-Gallant, “Performing Amputation: The Photographs of Joel-Peter Witkin,” Text and Performance Quarterly, 28, no. 1 (January 2008), p. 9.

15

Much of the work to reintroduce Böttner into twentieth-century art history has come from the curator Paul Preciado, who curated a monographic presentation of her work at Documenta 14 in Kassel in 2017, and her first and only retrospective in 2021: Lorenza Böttner: Requiem for the Norm at the Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery in Montreal, Canada. The exhibition has since traveled internationally, including to the Leslie Lohman Museum in New York City in 2022, where I was introduced to Böttner’s work.

Gemma Cirignano is an art historian based in Brooklyn, New York. She received her M.A. from the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University in 2023. Her research interests include the history of neon art, feminist and queer theories of artistic labor, and post-war and contemporary art. Cirignano currently works full-time as the Senior Researcher and Museum Liaison for Masterworks' art collection. Additional recent projects include contributing an essay to Nat Mayer Shapiro: Joy and Rigor (2024), research and fact-checking for Chryssa & New York at the Dia Art Foundation (2023), co-curating the exhibition Heterotopic Home: A Familiar Site of Daily Life at SPRING/BREAK Art Show (2022), and serving as editor-in-chief of The Genius List (2018-2021). Her writing has also been published in the Woman’s Art Journal, Artefuse, and Irradicant.