Misoo Bang

INTERVIEW

ISSUE I

2025Every girl I painted was me–vulnerable–with imagery such as suffering alone or locked in a cage. I wasn’t sure that I was painting myself at the time since I was also inspired by magazine covers or girls in media. Even though I wasn’t showing my work to people, I felt like I was able to express myself.

When I was 30, I was in grad school and I became a mom. It was a really exciting moment. I was happy, even if it was difficult and exhausting. During grad school, a big focus for me was trying to figure out why I was making the work. I was trying to figure out my intention. This time allowed me to dissect what I was making. And because I was in academia, I was trying to make academic sense of it. There are pros and cons to that because many of my paintings were very dark.

BT: Right, there isn’t always a language or acceptance for those internal and emotional spaces within academia, even if that is what the artwork encompasses.

MB: Exactly. So, I went to the library and decided to follow what interested me. I went to the criminal justice section and began to look at photos of victims because they resonated with me and grabbed my attention versus looking at the art section. I began researching victim’s photos, particularly children that had been abused. I started reading philosophy at this time too, trying to figure out why I resonated with this topic and how it affected my work. I began to ask: what am I doing? I was spiraling. At this time, I was drawing young girls that had been hurt or abused, which is what initially led me to the criminal justice section at the library. I still didn’t understand why I was creating this imagery. This also inspired the doll series, I bought some old porcelain dolls at a flea market and drew them. Instead of drawing them nice and pretty I twisted and contorted their bodies to reflect a sense of pain, rape, and abuse.

Around this time, I was back in the library finishing a paper and I noticed that the works I’d been creating and the research I had been doing all matched moments of my own childhood. I never repressed these memories, I never lost them. I was more-so accepting the fact that I had been raped and abused during my childhood. I was trying to find the language to describe those experiences since that language didn’t exist when I was ten. It all happened through force. I even felt guilty about it. I knew what was happening to me was wrong, but didn’t know how to process it. It was my biggest secret. So at that moment in the library, all the memories flew back to me. All the books I’d been reading, everything I’d been feeling, my artwork, it all made sense. I started crying, even through my art history lecture after the library. My professor was kind enough to pull me out of class to sit with me and ask if I was okay. Not all professors do that. She didn’t tell me I had to do anything specific, she was just there for me. Then, I stopped making artwork. After those memories flooded in I could not make any more narrative drawings. I didn’t know who I was, am I thirty? A mom? Am I the young girls in my paintings?

Because I was in school, I had to make artwork. Otherwise, I would fail out. So it became tricky, every time I tried to create it was a portal to the past. Abstract work helped with this. I started to create large abstract works where my anger and sadness could pour out. I did this for four years, no more narrative paintings, just abstract ink pieces. They got bigger and increasingly aggressive. Then I started to display them. I would rip parts of the works and display those, it felt like I was taking care of my ten-year-old self. Acknowledging her. The perspective and power these works gave me, along with being a mom, allowed me to find peace. I hugged my past self with the peace I found. This is what I wanted to do moving forward, show that understanding to other people. I finally felt I could move on.

Misoo Bang

Artists

Issue I, 2025

Burntout (BT): How are your series of works connected? Are they connected?

Misoo Bang (MB): It's very connected. When I think about it, it begins with how I became an artist. The full timeline, starting with my narrative drawing to abstract painting, the giant series, the lotus flower, and then to Buddhist painting. It's all different work but they are all connected. Everything is influenced by one another.

I started making art when I first came to America. The reason I began making art was because my English wasn't very good and I needed to communicate. So I chose to use a visual language. Instead of telling people how I feel or what I think, I thought I could draw and then show it to them. I didn't have friends at the time, so I painted. The artwork and the practice became my best friend…it helped me survive through that rough time in high school and through the language barrier. Many personal hardships were happening at that time as well, learning how to function with diabetes, my father passing, living with my mother for the first time and not knowing her very well, trying to make friends in high school, etc. My paintings were very narrative-driven as a result of this.

This is when I began the large portraits of myself instead of girls inspired by magazines. A lot of women were very sexualized in the media at this point. It caused me to reflect and ask why I was ever inspired by those images.

BT: That’s a great question. I don't think we generally ask ourselves that when we look at things that we're inspired by.

MB: Right, we also think it’s always the “right way” to show ourselves or what we should strive for. So, I changed this outlook and created self-portraits and called them Large Asian Girls. I collaged the surrounding space with popular Western media and pieces of Renaissance paintings, this depicted how small I felt living in America and being stereotyped as petite, tiny, and submissive in the media. After I started to show these paintings at galleries, other Asian women in the community wanted to model for my work. This is how the series evolved to the Giantess Series, painting survivors and victims of domestic violence.

This series is all about finding inner strength. I’m inspired by my models, once they see themselves in the painting they recognize their strength. That energy shines through. I’m grateful to paint them as a giantess. I did about thirty or more of those and then shifted again.

BT: I’m grateful you’ve brought awareness to the topic. There’s little education about domestic violence, at least that’s offered at a young age. It was romanticized in the media growing up, especially the passion and the patterns.

MB: Right, it’s become more popular to discuss within society but the default response to sharing your experience used to be shame versus protection or education. Nobody wanted to be attached to the terms ‘rape’ or ‘domestic abuse’. When I would show the Giantess portraits and give talks, I asked each model to send me a statement to read with the work. I would ask, “What do you want me to say on behalf of your experience?” Revealing that takes so much courage. But it reinstated that we are going to talk about this, no more silence. I want to celebrate that courage and power.

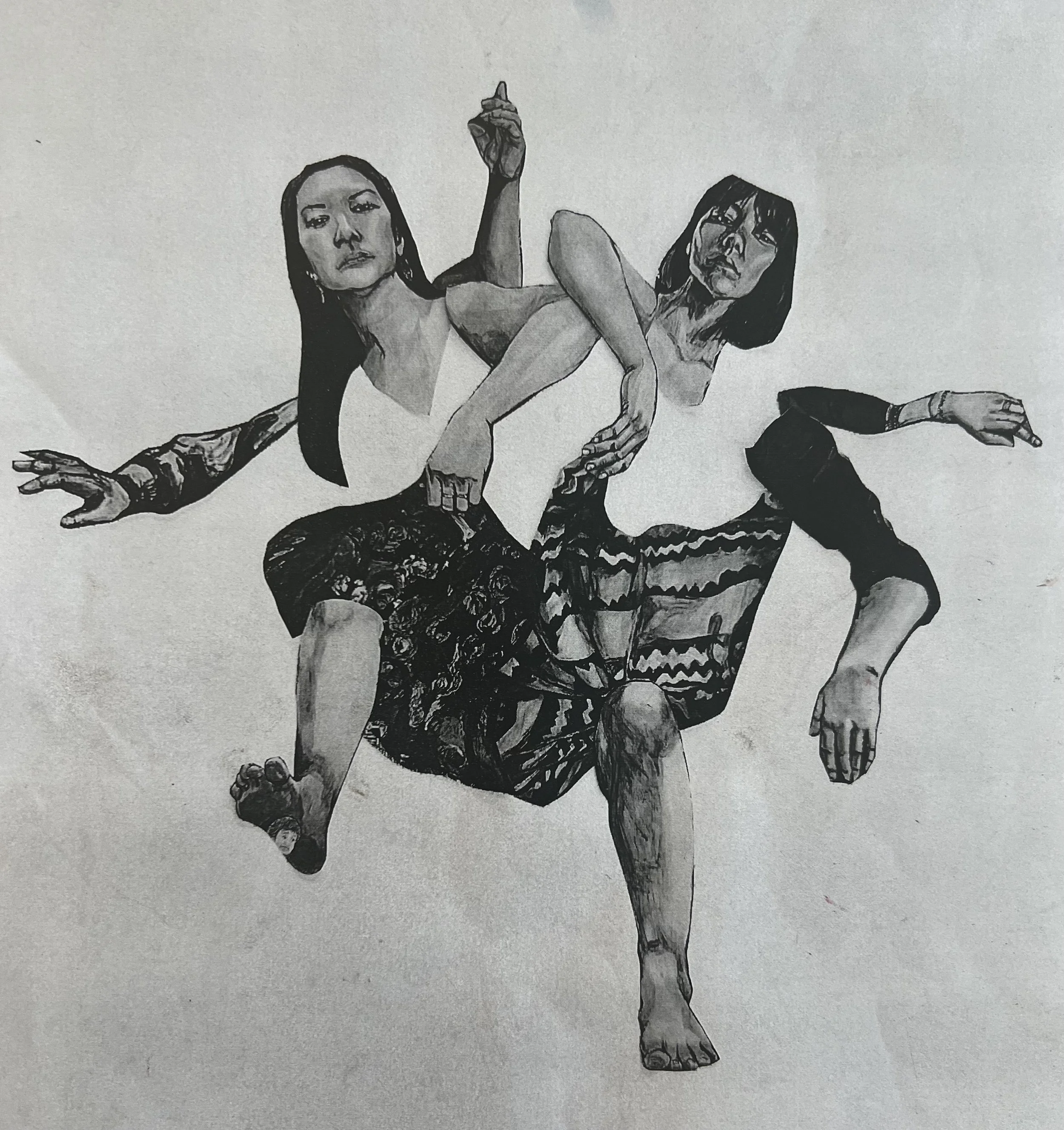

For each person, I go there with you. When we discuss the topic, I mean. The model sucks me into their experience so sometimes it’s difficult for me to know who I am and where I am while I’m listening. Sometimes I tap myself to get back into my body. We’ve formed a bond and understanding, the models and I, having gone through similar experiences in different ways. This work eventually inspired my interest in Buddhist painting, specifically the painting technique Taenghwa–I have barely scratched the surface of this technique, by the way, people who study this daily grind their soul into the painting process. I have studied it and made it my own. I’m interested in the concept in Buddhism that nothing lasts forever. That our health and happiness, but also our memories and pain don’t last forever. I wanted to visualize something beyond a giantess, something god-like. I studied Buddhism whenever I visited Korea and began drawing bodhisattvas. I wanted to add more peace to these paintings, rather than having the collages of Disney characters or Renaissance paintings surrounding the figure to have a bit less chaos. So I began the Lotus Flower Series where the giantess is in more of a peaceful state. I also printed out giantess paintings and would cut up the arms and legs of the figure and collage those together as well. For example, a figure would have two faces, four arms, or five legs. All of this represents that the giantesses are together, like sisters. They are bodhisattva in this way with the multiple limb imagery and they become more powerful. Within all of these is a critique of Western culture and is also a reflection of the rage and hecticness in my mind.

BT: Your work has such an intertwined visual representation of rage and peace. You allow yourself to express this with precision. The human-ness is still graceful.

MB: Right, I try to interpret that combination in my style. And put some humor in there. It becomes enjoyable and a kind of entertainment for me ha. It’s my form of meditation without sitting still.

BT: Lastly, what are you excited about now?

MB: This feels kind of funny to say in an interview. But, I am currently really into Disney. I'm a Disney fan yet I simultaneously use that visual research as a critique (ha). I think it stems from the fact that even though I’ve lived in America longer than Korea and I moved here over 25 years ago now, I still don’t feel like I belong. Probably because of how other people see me, they always ask things like, “Are you an international student?” Especially in Vermont. When I go back to Korea though, my friends and family treat me like a stranger too. They ask, “When are you going back home?” or they say, “You don’t even live here.” It’s like people can sense I’m not living there...until I answer back in Korean. I’m alienated in both worlds. All that to say, I feel like I belong when I visit Disney World because everyone is a stranger. I get into a line for a ride and people all ask one another where they’re from, I’m not singled out. I enjoy that moment of being welcomed and humanized. People are there from all over the country. I understand the capitalist system of it all and it is expensive. But for me, it’s worth it for three days of that welcome feeling. It feels like I can belong.

BT: It’s interesting how amusement parks foster the concept of being neighborly or elements of being nice, even if it’s a facade or small talk, you're being welcomed in as a fellow human. It's of course ironic that that feeling of belonging is found in a world of imagination.

MB: Right, even if they are strangers or crew members, there’s a familiarity and excitement in the air. It makes you feel like you’re a part of something. I think a lot of my artist friends laugh about me liking Disney. It’s very cheesy or stigmatized but I know many people share what I’m feeling.

Disney might seem like an unusual place to feel at home–but to me, it’s the perfect symbol of the American Dream: curated, controlled, and full of contradictions. It’s a miniature America, where fantasy masks inequality, and manufactured joy smooths over real discomfort. There are hierarchies, colonial narratives, and sanitized histories–but inside that illusion, I’m finally not asked where I’m from. I’m just another visitor. And in a country that often makes me feel invisible or out of place, that anonymity feels like a relief. The irony is stark: the only place I feel like I belong is inside a fantasy designed to sell belonging. I’m committed to continuing this exploration–what ‘home’ means not only to me but to others who’ve felt out of place in multiple cultures. This is where my next body of work is headed.

Misoo Bang is a Korean American artist who expresses her emotional narratives and storytelling through painting and drawing. Her recent works, The Giant Asian Girls and The Lotus Flower series, explore the intersection of gender-based violence and racial stereotypes faced by Asian women in the United States. Misoo’s work has been exhibited in galleries and museums both across the U.S. and internationally. She was recognized as an Emerging Artist of New England in 2019 and named a Vermont Artist to Watch in 2020. She currently teaches studio art classes at the University of Vermont and lives and works in South Burlington, VT. Misoo can be reached at misoo@misoo.org.